Reading

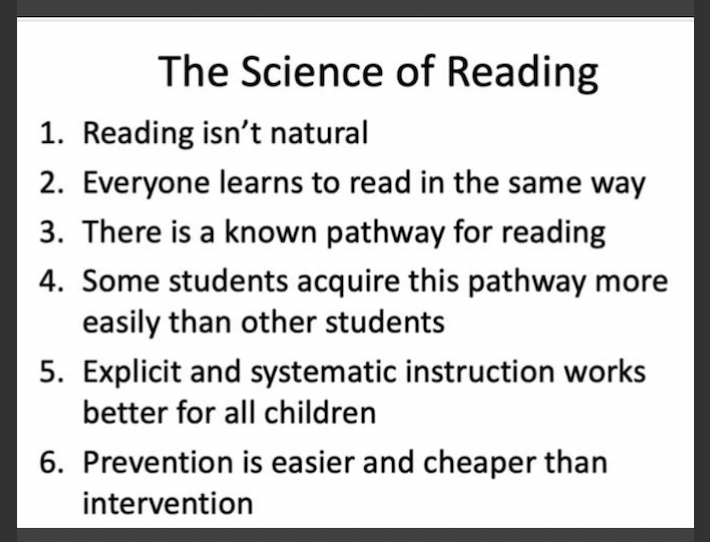

A great deal of research has been done on how we learn to read. Forms of writing appeared in human culture only about 5000 years ago which means reading is not a natural, evolved skill. “…[B]ecause there are not genes specific only to reading…reading has no direct genetic program passing it on to future generations.” (Wolf pg. 11)

If it is not an evolved skill then how does the brain learn to do it? Our brains have found a way to use the structures it already has to make sense of our written codes. “If there are no genes specific only to reading, and if our brain has to connect older structures for vision and language to learn this new skill, every child in every generation has to do a lot of work. As the cognitive scientist Steven Pinker eloquently remarked, ‘Children are wired for sound, but print is an optional accessory that must be painstakingly bolted on.’ To acquire this unnatural process, children need instructional environments that support all the circuit parts that need bolting for the brain to read.” (Wolf pg. 19) Dr. Stanislas Dehaene explains in the video below that the brain combines several systems we have evolved for other purposes and found a way to connect the sounds of our language to symbols we call the alphabet. Brain images of novice readers show a great deal of neural activity over many parts of the brain. When a young child is reading, the inner workings of their brain looks like a fireworks show! For expert readers, the required brain structures are used more automatically so less neural activity appears.

Surprisingly, we all use identical brain structures when reading regardless of the writing system or language. (Dehaene, pg. 71) This means we all learn to read the same way. While the effort needed varies from person to person the process is the same for us all. As Dr. Stephanie Stollar of the Reading Science Academy summarizes:

Learning to Read

We learn to read in stages. (Frith, 1985) (Dehaene pg. 200-204)

Stage One is at around age five and six and is called “logographic” or “pictoral”. The visual system in the brain views words much like it views things and faces. This is when children appear to be reading common logos such as “McDonalds” or “Pepsi” because they recognize features of the word such as the shape, colour, font, etc.

Stage Two is called “phonological” referring to sounds produced in spoken language. Children begin to learn the alphabetic principle that words have smaller parts in them called letters and that these letters are connected to speech sounds.

Stage Three is called “orthographic”. At this stage children begin to move beyond slowly decoding to more fluent reading. Stage Three readers are doing what is called orthographic mapping.

Orthographic Mapping

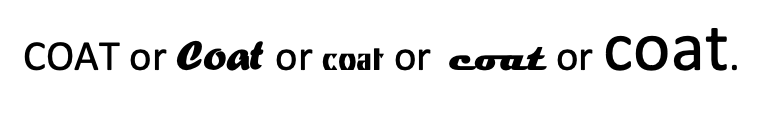

Orthographic mapping is the storage of printed words into long term memory. (Kilpatrick pg. 96) It is how we gain sight words (words we know so well we do not have to sound them out). This does not mean the words have been memorized. Words are not stored as word shapes in our visual memory. Rather they are stored as spelling patterns connected to oral pronunciations. It is a subtle but profound shift: the anchor for the written sequence of letters is the sound sequence of the word that is already in long term memory from having learned to talk in that language. (Kilpatrick pg. 101) Once a letter sequence is orthographically mapped it can be recognized regardless of its physical features. This is why we have no difficulty recognizing that this version of the word “coat” is the same as

We have mapped the sequence and can connect it to its spoken sound. If visual memory were being used then each of these variations of the word “coat” would have to be separately stored and recalled as needed. It is possible for our visual memory to store words, but visual memory is actually quite limited. Orthographic memory is almost limitless and easily able to hold the tens of thousands of words we read as adults. “Thus, orthographic memory involves a connection-forming process to which the oral phonemes [sounds] in spoken words are ‘bonded’ (Ehri, 2005a) to the letters used to represent those phonemes. The phoneme sequence of the word that is already established in the long-term memory acts as the anchor for the written sequence of letters used to represent that phoneme sequence. The perceptual properties of the letters are not important, as long as they are legible to the reader.” (Kilpatrick pg. 101)

Dr. Lynn Stone from the organization Reading for Life explains orthographic mapping in the video below.

Share’s Self-Teaching Hypothesis

Once all of the foundational pieces are in place for a child, they begin to teach themselves new words through independent reading. Those foundational pieces are: having a great deal of experience speaking and listening to language, phonological awareness, phonics knowledge, and decoding practise. When a child begins to read on their own, they can use their decoding skills to tackle new words and then use their knowledge of the spoken language (phonological skills) to anchor the new letter sequence in long term memory (orthographical mapping). “Then, after one to four exposures to that new letter sequence, all connections are made and secured. The sequence becomes instantly familiar and is not confused with similar-looking words with different sequences (e.g. trail/trial, silver/sliver). From that point on, the entire familiar sequence activates the entire spoken pronunciation as a unit because our eyes can simultaneously perceive all the letters in a given word (Rayner et al., 2011), so that whole sequence of letters is recognized as a stored familiar sequence. This is why it feels like whole-word recognition because of the speed and reliability of the recognition process when one encounters familiar letter strings.” (Kilpatrick pg. 101) That it only takes one to four exposures for a new word to become permanently part of a child’s long term memory is astounding! It explains why the amount of sight words a child knows will grow dramatically after they begin reading on their own.

Orthographic Mapping Around The World

Learning to read is a very complex process. It is an especially complex process for English language speakers. Languages that have simple spelling patterns are said to have shallow or transparent orthographies. This means that most, if not all letter symbols are matched to only one sound. With a 1:1 sound to letter correspondence, learning spelling patterns can be done fairly quickly for typical learners. Languages that have complicated spelling patterns are said to have deep or opaque orthographies. This means that many letters can have multiple sounds associated with them. This greatly increases the amount of spelling variances readers have to learn causing the process of learning to read to take a longer time.

The image below shows the percentage of reading errors made by students at the end of first grade in languages around the world. Notice that students in Great Britain had 67% errors in their reading. Students in Denmark had 29%, students in France had 28%. These greater amounts of errors are a reflection of how much harder the languages are to learn to read than others. They have opaque orthographies with complicated spelling patterns. Unfortunately, English is the most opaque of them all. “Italian children, after a few months of schooling, can read practically any word, because Italian spelling is almost perfectly regular. No dictation or spelling exercises for these fortunate children: once they know how to pronounce each grapheme, they can read and write any speech sound. Conversely, French, Danish, and especially British and American children need years of schooling before they converge onto an efficient reading procedure. Even at the age of nine, a French child does not read as well as a seven-year-old German. British children only attain the reading proficiency of their French counterparts after close to two full years of additional teaching.” (Dehaene, pg. 230)

Seymour, Aro & Erskine (2003)

Four Part Processing Model of Word Recognition

Here is a visual representation of the elements needed in learning to read. Read this image from the bottom and going up. Orthographic mapping occurs after learning the sounds of a language, its letter symbols, and phonic and decoding experiences. Once the alphabetic code is learned then layers of meaning and context are required to understand what is being read. This is accomplished by learning vocabulary, grammar, inferring, metaphors, etc.

A Note About Reading Targets

Different countries have different reading targets for their students. For example, the US requires reading instruction to begin in Kindergarten at age five but Finland does not begin teaching reading until students are age seven. Canada is in the middle with formal reading instruction beginning in Grade One when students are age 6. Why the difference? If a country has a transparent orthography, as Finland does, students do not need as many years of reading instruction to become proficient. Why the difference between Canada and the US? There are several reasons, some cultural and others administrative. For example, many states in the US have a school entry birthdate cut off in September or August. That means the youngest students in each grade are the ones born in August and September. Prairie Spirit School Division has a school entry birthdate cut off of December 31st. That means our youngest students are those born in November and December, possibly several months younger than students in the same grade in America. In the early grades, a half year can have a large impact on student readiness. If you are reading articles from the US about reading in the early years, a good rule of thumb is to add at least six months to the reading targets that are mentioned.

A very short summary

1. Reading must be taught. It is not an evolved skill.

2. The brain has only one way to learn how to read.

3. Reading progresses through the stages of pictoral, phonological, and orthographic.

4. Orthographic mapping occurs when known sounds for a word are connected to the word’s letter sequence and stored in long term memory.

5. Orthographic mapping is how we store sight words for instant recall.

6. Orthographic long term memory is almost limitless.

7. Once students enter the orthographic stage of reading they can self-teach themselves new words.

8. The English language has an opaque orthography with complex spelling patterns.

9. It takes English language learners many more years of school to learn how to read compared to students learning to read languages with transparent orthographies.

10. The Four Part Model of Word Recognition is a helpful visual for explaining how students learn how to read.

11. Different countries may have different reading expectations, even those sharing the same language.

References

Dr. Stephanie Stollar of the Reading Science Academy “A Brief Intro to Reading Science” video.

Frith, Uta (1985) Beneath the surface of developmental dyslexia. In Patterson, K.E., Marshall, J. C., & Coltheart, M. (Eds.), Surface dyslexia: Cognitive and neuropsychological studies of phonological reading (pp. 301-330). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Seymour, Philip H. K., Aro, M., Erskine, Jane M. (2003) Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies, British Journal of Psychology, Volume 94, pg. 143-174.

Seidenberg & McClelland (1989) “A Distributed, Developmental Model of Word Recognition and Naming” Psychological Review November.

Related Reading