Executive Functions

Executive functions are the skills we have practised and developed since childhood that give us the ability to make plans, enact our plans, and then review and improve our plans. Executive functions are necessary for human beings to be successful in relationships and in the world around them. They are how we self-regulate and show self-control.

Dr. Russell Barkley is an eminent researcher and clinician in the field of executive functions. Dr. Barkley has a particular interest in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) which is a form of interruption of executive functions. His books are the primary sources for the information below. For ease of reading, we have abbreviated the titles of the books when referencing them. Dr. Barkley’s book Taking Charge of ADHD will be noted as (TCA, 2013) and his other book we found pivotal to our reading called Executive Functions will be noted as (EF, 2012).

Dr. Barkley offers the following as a definition of executive functions: “…the use of self-directed actions so as to choose goals and to select, enact, and sustain actions across time toward those goals usually in the context of others often relying on social and cultural means for the maximisation of one’s longer-term welfare as the person defines that to be.” (EF, 2012)

Accurate but wordy for everyday use!

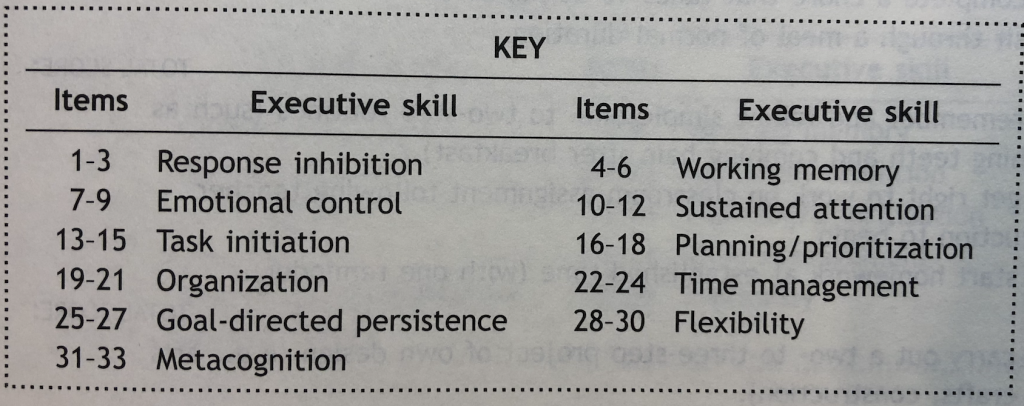

Peg Dawson and Richard Guare, authors of Smart But Scattered (2009), have a chart in their book that lists executive function skills in simpler, easier to visualize language. The numbers under the column called “Items” refer to questions asked in a questionnaire they have created to help children and adults determine their executive function strengths and weaknesses.

Key Components of Executive Functions

(TCA, 2013 pgs. 55 – 70)

1. Self-Restraint or The Mind’s Brakes

Our ability to delay our reaction to something is much longer than other species. That period of delaying actions can be for a short length of time (seconds) or long (weeks). Self-restraint takes effort and the greater the impact of the stimulus the greater the effort needed to delay an action.

2. Self-Awareness or The Mind’s Mirror

When we delay a reaction, be it for a short or long length of time, we use the wait time to think things through. This means that not only are we able to notice things in the environment around us but that we are able to notice things about ourselves. Humans are able to do more than simply take in information through our five senses. We can reflect on our own thoughts and emotions and change our behaviour based on those reflections.

3. Self-Directed Imagery or The Mind’s Eye

Our awareness of ourselves and of memories of what we have done in the past gives us hindsight (memories of actions) and foresight (imagining possible futures). Hindsight or learning from our past informs behaviour in the present. Foresight allows educated guesses about what might happen next. While foresight does not guarantee accuracy about the future it provides more support than random guessing.

4. Self-Directed Speech or The Mind’s Voice

We talk to ourselves and this is normal – whew, relief! There is a developmental progression of internalized speech. Toddlers first talk to others and then they begin talking to themselves while playing. At preschool and early elementary ages self-talk is present but it becomes much quieter so no one else can hear. Eventually children fully internalize their self-talk so it is silent and through their mind’s voice. Self-directed speech helps us guide and control our behaviours in order to reach a goal. It also helps us reflect on past actions and analyze our memories in hindsight.

5. Self-Directed Emotions or The Mind’s Heart

When we delay our reaction we give our brain time to analyze the event in two different ways. One way is the emotional meaning we give to the event (feelings) and the other is the information surrounding the event (context). If we can put our feelings briefly on pause we can react less emotionally and instead more thoughtfully analyze the situation. It is not that emotions are bad but rather that to have emotions always ruling our decision making would interfere in our relationships and with reaching our goals.

Our feelings help us to decide whether something is positive, unpleasant or neutral. How we feel about something motivates our action towards it. How we feel about a situation is a major factor for our level of persistence and determination. This is also called will power.

6. Self-Directed Mental Play or The Source of Problem Solving and Innovation/Creativity

First, we take in and analyse the message and information we are receiving. Second, we play each separate part of the message against all of our previous memories about similar messages and situations. We have the ability to sort through many possible reactions and to then choose an answering behaviour that we think will be most successful or appropriate. Vital to this process is wait time.

When encountering new information for which we have no past experience we have the ability to create new ideas. In Dr. Barkley’s words: “When we inhibit our response and wait, we can take old ideas and rules and break them apart, combining them with those of other ideas and rules to come up with entirely new combinations. We call this process problems solving, and as humans we are masters at it. People who cannot inhibit and delay their responses to what’s happening around them will be less adept at devising solutions to problems they have encountered.” (TCA, 2013 pg. 65)

In children this process of analysing messages and considering reactions is often practised through play. Play allows children to test out “what if” arrangements of events and responses to them (EF, 2012 pg 90). They are building a reservoir of memories to use as reference points to solve future problems. The observable play of childhood eventually becomes the internal mental play of adult problem solving and innovation.

Hierarchy of Executive Functions

Dr. Barkley has theorized a hierarchy of executive functions. It is useful to know this hierarchy in order to understand why executive functions have evolved in humans far more than in other animals.

The Instrumental/Self-Directed Level: The above mentioned six executive functions allow an individual to not only react well in the moment but to also change their behaviour to affect (and hopefully improve) their future.

The Self-Reliant Level: Children grow from dependency upon their parents to independence as adults. Executive functions give individuals the ability to learn self-care skills as well as to determine when situations are not safe or when others do not have their best interests in mind.

The Social Reciprocity Level: Reciprocity means sharing, turn taking, give and take with others. This begins within the family and eventually moves outside of the family to friendships, community relationships, and work connections. We learn to assist others with the expectation that they in turn will assist us when called upon.

The Social Cooperative Level: This is when people come together to work towards a common goal. This kind of teamwork helps us reach goals that are larger, more complex, and more rewarding than what could be accomplished alone.

How to Improve Executive Functions

Executive functions take years to develop and often require explicit, clear modelling and teaching. Dawson and Guare suggest the following ten principles for improving executive function skills with children. (Smart But Scattered, 2009 pgs 71-79)

1. Teach deficient skills rather than expecting the child to acquire them through observation or osmosis.

2. Consider your child’s developmental level. There are age appropriate benchmarks which can help guide your expectations for your child.

3. Move from the external to the internal. Give cues or supports to help develop a routine or expectation.

4. Remember that the external includes changes you can make in the environment, the task, or the way you interact with your child.

5. Use rather than fight the child’s innate drive for mastery and control. Build in routines, choices, and small steps that empower your child.

6. Modify tasks to match your child’s capacity to exert effort. Know the difference between tasks your child finds hard to do and tasks they can do well but just don’t want to.

7. Use incentives to augment instruction. For some children independently completing a task is reward enough, for others it isn’t. Some children can delay gratification for longer and work towards a larger reward. Others cannot and will need incentives more often.

8. Provide just enough support for the child to be successful.

9. Keep supports and supervision in place until the child achieves mastery or success.

10. When you do stop the supports, supervision, and incentives, fade them gradually, never abruptly.

Executive Functions At School

Success in an academic setting requires executive function skills such as cognitive flexibility, working memory and inhibitory control. The following two quotations are from a paper by Drs. Zelazo, Blair & Wiloughby about the role of executive functions in education:

“EF [Executive Functions] have both direct and indirect roles in classroom learning. EF skills directly make it possible for students to sit still, pay attention, remember and follow rules, and flexibly adopt new perspectives…Children who arrive at school with well-practised EF skills may learn more easily, and this may initiate a positive cascade of indirect effects, such as liking school and being motivated to work hard. More research on these indirect effects is needed, but children with good EF skills who learn more easily may be more likely to enjoy school, feel optimistic about their own learning potential (e.g. adopt a growth mindset; Dweck 2006), and get along with teachers and peers.” (pg. 19)

It is part of school readiness to have aspects of self-regulation such as being cooperative, considerate of others, and believing that one can learn. (pg. 21)

A Very Short Summary

1. Executive function are brain-based skills that help us have successful lives.

2. The six key components of executive functions are self-awareness, self-restraint, hindsight and foresight, emotional regulation, self-motivation, and mental play.

3. Executive functions assist in success for individuals and in success for communities.

4. Executive functions must be taught and supported over time in order for a child to learn them well.

5. Age appropriate development of executive function skills are required for academic and social success at school.

6. Executive functions take decades to fully develop.

References

Zelazo, Blair & Wiloughby, “Executive Function: Implications for Education”, paper for The National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, 2016

Related Reading

Nancy Tarshis & Michelle Garcia Winner