Speaking and Listening

The purpose of speaking and listening instruction is to guide students as they learn to use language and its conventions to construct meaning. Students practise speaking by learning to adjust their volume, tone of voice, vocabulary, and sentence structure to the situation. Students practise listening by demonstrating attentiveness through their body language and facial expressions.

General language skills that students practise in Grade One are to:

– speak in simple complete sentences

– speak in grammatically correct sentences

– answer questions in complete sentences

– use common social greetings and expressions (e.g. “Thank you”, “Good morning”)

– express understanding of topics, themes, and issues

– choose and use words to add interest or to clarify

All people talk for a purpose. Sometimes talking is used for an informal reason, sometimes for a more formal reason. In Grade One, students improve their speaking and listening skills through practising conversations, discussions, presentations, and by giving directions.

Conversations

Conversations are informal speaking and listening opportunities for children. Students are encouraged to have conversations with their classmates, recess buddies, Care Partners, Reading Grandparents, and of course, with the adults around them in the school. Conversations require turn taking, listening attentively, staying on topic, responding to the comments of others, and asking questions. These behaviours permit a back and forth exchange in which one participant’s comment or question builds on another’s contribution. Conversations give students a chance to clearly express their knowledge, opinions, likes, and dislikes to others in a relaxed setting.

Discussions

Discussions are more serious than conversations. Discussions require students to think critically about what they are saying or hearing as they seek to learn more or to make a decision. It involves students asking and answering questions about the information being communicated in order to gather details or to clarify a confusing point. Discussions can arise from something heard (a conversation, presentation, dramatic play, video), something read (book, pamphlet, magazine, poster, sign), or from one’s own writing (story, poem, report). In Grade One, common questions in discussions tend to be about details, order of events, motivations, and points of view. This sounds complicated but these ideas are really no more that asking Who? What? Where? When? How? and Why? questions. Through discussions, Grade One students learn to tell the difference between making a comment and asking a question and that it is desirable to seek information until something is understood to their satisfaction.

Presentations

Presentations require sharing information in such a way that listeners can follow the presenter’s line of thought. The style and level of organization in the presentation will vary depending on the audience and purpose. In Grade One, students practise presenting during their Sharing Time (Show and Tell). They are expected to describe people, places, things, and events while expressing their ideas and feelings clearly. Listeners are expected to make the presentation an enjoyable event by asking questions or making positive comments about what is being presented. Presentations such as reader’s theatre, poetry recitations, and our annual Christmas Program are more formal in nature. Students are taught to adapt their speaking skills and listening behaviours to the occasion accordingly.

Sequenced Steps

Students need to learn how to give or listen to a series of steps. In many day-to-day situations we make simple to-do lists for ourselves in which the order of events is not important. However, other life situations require actions to be completed exactly in order to prevent disappointing or unsafe results. By the end of Grade One students are expected to give a clear sequence of instructions and also to independently carry out a sequence of instructions. Some ways to practise these skills are through learning classroom routines with multiple steps, writing “how to” books, creating maps with step by step directions, using recipes, etc. Learning how to follow specifically sequenced directions gives students a sense of independence and teaches them to pay attention to detail.

Research on Speaking and Listening

Jean Gross’ book entitled Time To Talk is an excellent collection of speech and language research, activities, and resources. She suggests that the goal of language instruction is to model and improve informal language for children and to teach and expand children’s formal language. “So the task for school improvement seems to me to move children from everyday conversational language to disembodied formal talk – talk which, unlike informal conversational talk, does not depend on seeing what is happening for comprehension…” (pg. 18)

Practising speaking and listening also improves student’s vocabulary. Vocabulary knowledge has a significant impact on children’s reading comprehension. The number of words that mean something to a student is called vocabulary breadth. How well a student knows how to use those words is called vocabulary depth. Current research tells us that vocabulary depth is a stronger predictor of reading comprehension than vocabulary breadth. (pg. 93) More information on increasing vocabulary can be found on the “Reading” page of this blog.

Another reason for focussing on children’s speech and language skills is to develop metacognition. Metacognition is the ability to reflect on one’s own learning and it is highly dependent on talking. “Only through discussion can children come to an understanding of how they learn and what strategies work best for them.” (pg. 74)

There are many ways to encourage talking in a classroom. The following are situations that encourage students to talk without necessarily being teacher-led: (pg. 74 – 90)

– a situation with a surprise

– children asking the question

– children giving the instructions and descriptions

– collaborating

– giving an opinion

– debating

– using technology

– reminiscing

– drama and role play

– philosophy for children

Teaching Listening

Listening is an active skill with strategies that can be taught. Listening skills are developmental and change in complexity as a child grows from birth to school age. Children need to be taught that different situations require different types of listening:

– appreciative listening is used when listening to music, poetry, storytelling etc.

– critical listening is used when differentiating between fact and opinion, deciding whether to agree or disagree with a position, etc.

– empathetic listening is used when listening to the emotion being conveyed or the intent of the words

Good listening behaviours include looking at the person who is talking, sitting still, staying quiet so everyone can hear, and listening to all of the words said. (pgs 105 – 107)

Early Language Development

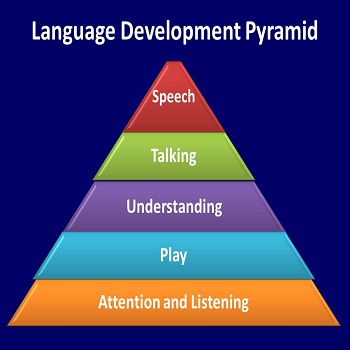

The Language Development Pyramid is used widely by Speech and Language Practitioners (SLPs). It shows the development of language and communication skills, the level above building on the skills formed in the level below. (pgs 26 – 34)

1. Attention and listening skills – children need to be able to hear what is being communicated to them and also to be able to sustain their attention in order to take in the message.

2. Play and interaction skills– children learn cooperative skills from playing together as well as a great deal of language knowledge. Besides expanding their vocabulary, play events help children understand that things and actions have words associated with them.

3. Understanding language – also called receptive language, which means what we understand from the language of others. Children need to understand a word before they can use it.

4. Talking – also called expressive language, which means developing grammar and vocabulary through talking to others. Children’s speech begins with single words and increases in sophistication over time.

5. Speech sounds – also called articulation, which means forming sounds correctly and fluently. It takes children time to fully develop accurate sound pronunciation, particularly the r, s, and th sounds.

Some versions of the Language Development Pyramid include a sixth layer called Pragmatic language. This refers to understanding conversational elements such as facial expressions, body movements, tone, volume, inflection, knowing when and how long to speak, and so on.

Factors in Language Acquisition

Research has identified key factors in supporting young children’s language acquisition. Two studies have particular significance. One study is from the National Literacy Trust (UK) and the other from the International Centre for Language and Communicative Development (LuCid). These reports suggest the following are very important for developing children’s language:

1. The amount of language spoken to a child. Speaking a lot to a child helps improve how much the child will speak. Other factors that matter are making sure the speech is directly to the child, that it is more than just giving commands, and that it uses complex and varied vocabulary.

2. Sensitivity to the child’s language level. Children improve their own speech more when the speech directed to them is at their language level. Often, but not always, this is a level that is connected to their age (baby talk compared to toddler talk).

3. The extent to which adults cue in and respond sensitively to what a child is trying to communicate. This long-winded sentence can be rephrased using a tennis metaphor of “serve and return”. When a child speaks (the serve), they need a response from the person they are directing their speech at (the return). If they regularly do not receive a response, they will not initiate speech as often.

4. Managing screen time. There is no substitute for conversations with real people. This does not mean you need to ban technology – conversations that happen through technology to another person can also improve speech growth. A child who is exposed to a great deal of screen time will still improve their speech skills as long as time for conversation with others is not lessened by the time spent with a screen. In other words, speaking time needs to be happening in addition to the screen time.

5. The way adults talk with children. Children learn more when adults pick up and follow the child’s topic or focus of attention. It is particularly important with very young children to talk about the topic while the child is focusing on it rather than later on.

6. Reminiscing about events. “Another very effective form of developing young children’s language is reminiscing about events that the child and their ‘communication partner’ have jointly experienced. This provides a motivating and meaningful context to move language on from describing the here and now to encompass things that are not actually present. It also helps children develop narrative skills that research shows are very important throughout school.” (pg. 32)

7. Sharing rhymes, songs, and books. Reading books, saying rhymes, and singing songs to a child exposes the child to words and sentence structures not commonly used in conversation. Sharing books should start early. Research shows singing, saying, and reading favourites over and over again is very effective for enriching children’s speech.

8. Avoiding background noise. It is difficult for most people to give their full attention to something when distractions are present, and this is especially true for young children. Children learn more from conversations and interactions when background “white noise” is eliminated such as music or television.

9. Opportunities for interaction with other children. Good news – the grown up does not have to do all of the teaching! Children learn a great deal about speech and language from each other when they play together.

10. Continued use of the home language when children are growing up bilingual. Learning a second language happens the same way the first language is learned. However, a child needs a firm foundation in the first language before tackling an additional language. This allows them to have vocabulary and sentence structure knowledge from the first language to link to the second language.

Language Disorders

If your child appears to be having difficulty with their expressive or receptive language, or with their articulation, we make a referral to our school Speech Language Pathologist (SLP). The SLP will assess your child and determine a course of action to be taken. This course of action could be exercises and activities for you to do at home with your child or it could be to have your child work directly with the SLP at school. Language disorders, while not frequent, are also not uncommon. “Irrespective of disadvantage, and irrespective of wider societal factors like time spent on TV and texting and computer games, international research looking at children of various ages shows that around 7 percent of children have a biologically based language disorder that makes it difficult for them to process language.” (pg. 16)

Language and Behaviour

Children want to communicate. When they feel they are not understood or when they are having difficulty understanding they can become frustrated. Sometimes they express their frustration with words, sometimes with actions. “Equally, it may be that it is children’s difficulty in communicating their needs to adults and peers in school that leads directly to behaviour difficulties….Children with language disorders often lack verbal strategies to manage in the classroom and may only take in one or two words of what is said to them. This can lead to failure following instructions which can be perceived as ‘naughty’ behaviour by the class teacher. Similarly, children with language disorders have difficulty following playground rules, and often misinterpret jokes from peers as other children ‘making fun’. The frustration and inability to respond leads to more disruptive behaviour and increased risk for social, emotional and mental health problems in the longer term.” (pg. 10) Helping children avoid the pain of communication difficulties is yet another reason schools focus on speaking and listening skills.

Language development is also connected to Executive Function development. “Another hypothesis lies in the idea that language is vital for self-regulation – developing the ability for internal talk that enables children to label and manage emotions and focus attention. This may underpin the finding that vocabulary at age two is a good predictor of how well children behave and manage their emotions at age six.” (Clegg et al., 2015) You can go to the “Executive Functions” page of this blog to understand more about self-talk and self-regulation.

A Very Short Summary

1. Different situations require different vocabulary, sentence structure, volume, and tone of voice.

2. Common scenarios for talking are conversations, discussions, presentations, and giving directions.

3. The goal of speech and language instruction is to enable students to move from speaking about concrete ‘here and now’ events to more abstract, global concepts.

4. Opportunities in the classroom to speak in authentic, ‘real-life’ situations improve student’s speech and language skills greatly.

5. Students need to be taught that listening is an active event that they deliberately participate in.

6. Early language development progresses through predictable stages of growth.

7. There are known, research proven factors that impact language acquisition.

8. Language disorders in children are not uncommon and are treatable.

9. Disruptive behaviour from a student may be how they are communicating their inability to express themselves through language or their inability to understand the language used around them.

10. Language must be acquired in order to develop self-talk. Self-talk is necessary for the development of executive functions.

References

Louisiana Department of Education ELA Guidebooks

https://www.louisianabelieves.com/academics/ela-guidebooks

Related Reading