Cognitive Science in the Classroom

Comprehension of what is read, spoken, and created is the overarching goal of learning in all subjects. When faced with something we do not understand we slow down the rate of input and reread-relisten-review. We “work” the material until the meaning becomes clear. If a student is having difficulty with understanding something there are many factors to consider why: (Shanahan, 2018)

- ability to pay attention for an age appropriate length of time

- difficulty and complexity of material

- insufficient background knowledge

- whether the questions being asked are phrased as open-ended or closed-ended

- number of exposures to the material

- answering from memory or having access to material

- questions asked immediately after exposure or time delayed

- and more……

As you can see, the reason why there may be interference with comprehension is multi-dimensional. Several things can prevent someone from being able to understand material they are presented with.

Cognitive science connection: thinking is hard work and there are many factors that can interfere with thinking.

Learning Across Subjects

Types of skills and strategies are often thought of as specific to the particular subject – when it is math time we use math skills, when its reading time we use reading skills, etc. However, when the human brain is learning something it does not differentiate between “math stuff” and “reading stuff”. Our brain hardware reacts consistently to the new learning regardless the material. What has been researched over the past several decades about our human ability to learn is amazing! Three big ideas from cognitive science that are very impactful to our teaching are the gradual release of responsibility, the proven strategies for effective learning, and a skills and strategies continuum.

Cognitive science connection: the human brain is consistent across gender, age, and culture as to how we learn things.

Gradual Release of Responsibility

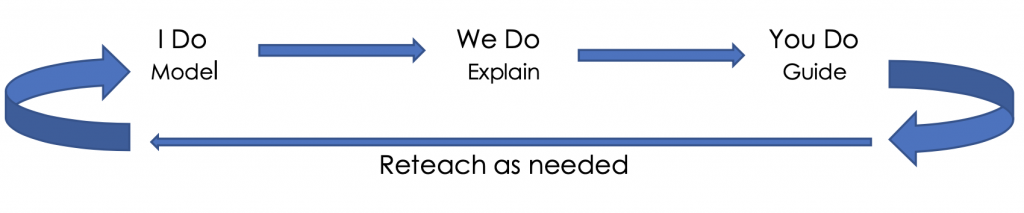

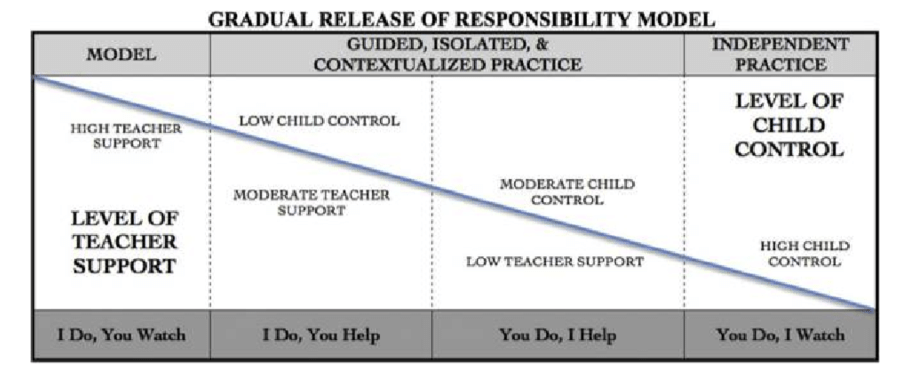

I do, We do, You do (Shanahan, 2018; Pearson & Gallagher, 1983)

A foundational teaching practise is called the gradual release of responsibility. When teaching something new to students, teachers will first model and show the idea, then we offer guidance as the students use the idea, and finally we step away supporting the students only when necessary as they use the idea independently. A short hand reference for this framework is first I, the teacher, will do it, then we will do it together, and finally you get to do it on your own. There is not a set time limit for moving through the stages of ‘I do, We do, You do’. Sometimes the students easily absorb the learning material and we can more quickly release responsibility, sometimes the modelling and explaining parts are longer and more intensive. If students are not understanding the lesson then we attempt to diagnose why, paying attention to the many things that can impact understanding. All of this taken into consideration helps determine what level of support is needed for students during the lesson. The goal is independence in which a deliberately taught strategy becomes a more reflexive skill for the students. Until that is achieved we reteach by repeating the ‘I do, We do, You do’ cycle as long as is necessary.

Cognitive science connection: novices do not think about information the same way experts do. Novices need support to become experts.

Effective Learning Strategies

(The Learning Scientists website)

The basic routine of school is that students commit information to memory through many types of experiences presented to them and then they show what they remember to teachers. We ask students to retrieve ideas from memory as a way to ensure that information they are meant to have learned has found a secure home in their long term memory. In daily classroom work we have students practise what was taught to them in order to have them internalize the information. The content needs to move from an episodic memory (day to day things) and instead become a semantic memory (integrated into larger concepts). This means much more than boring repetition that is often referred to as “drill and kill”. Research tells us that the following are the most useful techniques for helping information become part of long-term memory.

- -spaced practise

- -retrieval practise

- -elaboration

- -interleaving

- -concrete examples

- -dual coding

Having knowledge of how memory works and the practises that best support anchoring ideas into memory helps both our teaching and student learning become more efficient.

Cognitive science connection: what you practise and pay attention to is what you remember.

Skills and Strategies

(Afflerbach, Pearson & Paris 2008; Shanahan, 2018)

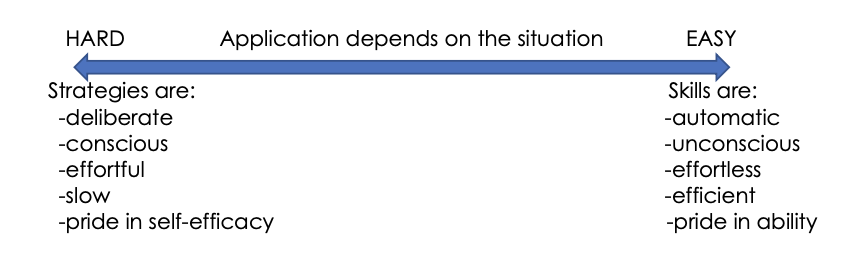

To some, the words “skill” and “strategy” suggest a learning sequence such as you need skills to learn strategies or you need strategies to learn skills. Other people use these terms interchangeably. The difference between skills and strategies is less about a hierarchy and more to do with a continuum. Imagine driving down a highway. At times you can set the cruise and go on automatic and at other times you are required to slow down and pay a great deal of attention. Automatic driving does not necessarily mean you are a good driver and neither does slow and careful driving. You are simply responding to the driving conditions and doing what is necessary to drive well. In the same way using skills and strategies is situational to the learning material being presented to the learner.

Strategies are what we use when we are experiencing difficulty. When an idea is hard to learn we slow down and make a conscious effort to make sense of things by using strategies that we have discovered or that have been taught to us.

Skills are strategies that are automatic and do not require much thought. When something is easy to do it means the strategies we have mastered are being used effortlessly and often unconsciously. The strategy is now called a skill. Maybe the job at hand is very easy or maybe you have practised long enough so that what you are doing has become automatic. Either way you are accomplishing the learning with great efficiency or we would say skillfully.

When referring to skills and strategies one is not more advanced than the other. Both are needed in order to learn new things. The same action could be either a skill or a strategy – it depends on the situation. What teachers do a great deal of is helping students recognize when they have moved too quickly and when they need to slow down and be more deliberate in their learning. Errors in student work tells us that a review of strategies is needed in order to improve understanding.

Common strategies that assist with improving how we construct meaning out of something new or hard to learn are:

- monitoring comprehension

- activating and connecting to prior knowledge

- asking questions

- inferring and visualizing

- determining importance

- summarizing and synthesizing

When students are facing new or complex material the teacher will work through it with them showing how to apply these strategies. The goal is to have students comfortable with using the strategies independently when they are faced with something they find challenging. When students are learning easily it is because these strategies are dissecting the information as effortless skills quietly working in the background of the student’s thought. There are many other strategies that students need to learn that are specific to different subjects. For example, sounding out is needed for reading, letter formation is needed for printing, adding and subtracting is needed for math, etc. The strategies listed above are more universal and can be applied across any learning situation.

Cognitive science connection: schemas (knowledge webs) are built first with surface structures (facts, skills). Then surface structures must be practised until they can be remembered with ease. Only then can thinking reach to deep structures and allow transfer between situations, creation of new products, critical thinking, etc.

Learning Taxonomy

Teachers don’t use the words “learning taxonomy” very often in our day to day business but learning taxonomies are very important in how we see student learning. Learning taxonomies are classifications of kinds of learning. They provide a framework with which to understand different types and degrees of thinking. Researchers have organized human learning into many taxonomies – it is a very big topic! Below are two of the more commonly used taxonomies which you may find useful.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

(Bloom 1956; Anderson et al. 2001; Ben-Jacobs 2017))

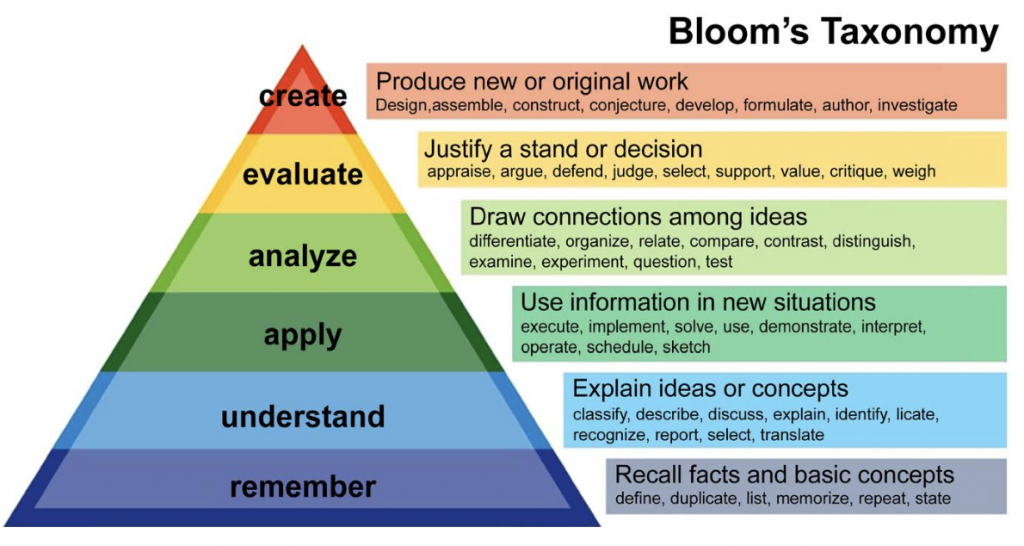

Blooms taxonomy was first proposed in 1956 by Dr. Benjamin Bloom. The names of the categories have been revised and slightly adjusted over time. The bottom categories represent actions associate with surface structures of learning (facts, skills). The top categories represent actions associate with deep structures of learning (transfer, critical thinking, creating).

Ellis and Worthington’s Forms of Knowledge

(Ellis & Worthington, 1994)

It is possible to reflect on the field of human learning by using multiple learning taxonomies at the same time. One framework does not cancel out another because learning is so multi-faceted. Dr. Ellis and Dr. Worthington proposed the following Forms of Knowledge classification system in 1994:

- Declarative Knowledge – the facts that we know

- Procedural Knowledge – the skills we know such as how to do something

- Conditional Knowledge – knowing when and where to use our knowledge

The Forms of Knowledge taxonomy provides a complimentary view of learning to Bloom’s Taxonomy and both, as with other taxonomies, are useful for teachers and students.

A Very Short Summary

1. There are many reasons that make thinking and learning hard to do.

2. Learning happens the same way in all human brains.

3. Research has shown us that there are known effective learning strategies.

4. Novice learners need support from those with experience when learning something new.

5. Skills are automatic. Strategies are deliberate. You consciously slow down a skill and use it as a strategy when learning is harder.

6. Learning Taxonomies help us understand different kinds of thinking and learning.

References

Afflerbach, Pearson, Paris “Clarifying Differences Between Reading Skills and Reading Strategies” The Reading Teacher, 61(5) pp 364-373)

Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001) “A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete edition)” New York: Longman.

Ben-Jacob, Marion G. “Assessment: Classic and Innovative Approaches”, Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2017, 5, 46-51

Bloom, Benjamin S. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (1956). Published by Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. Copyright (c) 1984 by Pearson Education

Ellis, E. S., & Worthington, L. A. (1994) Research synthesis on effective teaching principles and the design of quality tools for educators (Technical Report No. 5). Eugene: University of Oregon, National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 386853)

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(83)90019-X

Shanahan, Timothy (2018) “Comprehension Skills or Strategies: Is there a difference and does it matter?” Reading Rockets May 25 blog post

Shanahan, Timothy (2018) “Where Questioning Fits in Comprehension Instruction: Skills and Strategies” Reading Rockets June 1 blog post

The Learning Scientists Website with free downloadable material: https://www.learningscientists.org/

Related Reading